Vhils loves cities: their speed and their laziness, the time they take or how fast they go, the way we inhabit them. And Vhils doesn’t forget those who inhabit the cities when he looks at houses and streets. Just like lovers carve their names on trees in gardens, he digs into walls looking for the lives of those who live in the cities in the memory of houses and walls. Lisbon holds the place of special Muse in his work: he gazed upon it from afar, from the Tejo south bank, and as a teenager it was there that he lived the underground adventures of any street and graffiti artist, drawing pictures, writing words, looking for a meaning for himself and for the world around him. It’s in Lisbon that most of his work can be seen, and his pieces form a pattern which place the city on the trail of a themed global tourism which is growing in popularity.

In 2013, I visited his studio in the Santos quarter, in Lisbon.

It’s our first meeting after a few years without having seen each other. From the invitation to join the artists group who opened the Contemporary Art Museum in Elvas – António Cachola Collection, precisely seven years ago, and now, 2014, Alexandre Farto (his name on his birth certificate) has gone around the world more than once. At the time, he was 20 and only he knew the future he wanted for himself. In Elvas, he worked in a quiet and focused manner, just like today; and he laughed, just as he does today; he helped, as he helps today, his colleagues who were building other pieces around the military warehouse in Nossa Senhora da Conceição. On the outside wall, he painted a scene of war and urban violence and, on the inside, he put up an installation which evoked the same setting. It was not a glorification, nor a fascination for the aesthetics of strength: it was an accusation of war atrocities.

Alexandra opens the wavy door to a workshop. So far, nothing I didn’t expect. He’s older too, of course, but (and this is the first surprise) he looks younger. That is: the weight of his beard is overshadowed by how often and how long he smiles for. But he’s perhaps more nervous than before: except for his smile, everything else happens very fast in his body and his words – because now he has a lot more to show me. And that’s the second surprise: how can he fit so many things in such a small space, and how can such a small team make so many things? Along the entire length of a wall there are piles of posters taken from walls, they look like rubbish, but they aren’t – or aren’t any longer. Along another wall there are doors and shutters taken from houses which were demolished. There are also metal plates which have been worked with acid to form images and sentences. Some doors have been excavated with gouges, others have been lasered; and faces and decorative patterns are born on those unexpected media. At the far end, some (many) finished pieces await their exit orders to move on to exhibition or simply to be reworked on. In fact, Farto’s works stem from many ideas which he throws away, adapts, refuses and overcomes: whatever he now rejects will return later; whatever he can’t materialise straight away will wait as long as it takes to be reborn. Along a corridor, some new sculpting experiments with cement, or older experiments with resins. In the latter, urban posters are pinned onto a transparent casing, like urban bodies preserved on neutral ground for future memory. A little further back from that corridor, a room for technical and administrative work: that’s where his closest collaborators are, thinking about the design for the catalogues and the website, managing invitations and travel arrangements, calculating the laser cuts to be applied to the Styrofoam which he uses to build his face-scale models of cities.

It’s no pun to say that faces are the most visible faces of his art:

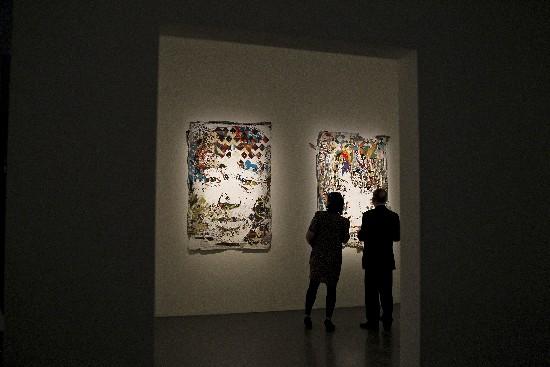

human faces on the faces of houses and walls; cities which acquire the faces of their inhabitants or which recreate faces they see on the other side of the World. In the exhibition we have just held this Summer at the Electricity Museum, in Lisbon, there was a large world map showing his main areas of activity outside Portugal. There was hardly a time zone where his name was not printed. Sometimes the pins fell right on the Ocean, and when we looked closer it was a façade he had excavated in Honolulu, Hawaii… More well-known were his projects in a favela in Rio de Janeiro and in a poor neighbourhood in Shanghai. That’s when Vhils’ social intervention project became clear: by working in neighbourhoods where the residents were about to be evicted to give way to beneficiaries of high-end real estate projects, showing on the walls, in large scale, the faces of the people being sacrificed was a form of denunciation, of raising public awareness, and of peaceful resistance.

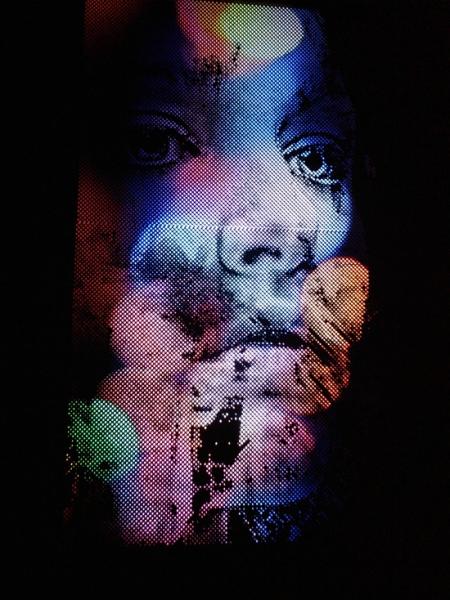

One of the issues we discussed the most was the adaptation of this type of art – which is on an urban scale and usually achieves immediate communication, due to the media used, the time and place and the urban public inherent to it – to the inside of a museum, which is smaller in size, is built from very different materials from the ones used outside, and attracting visitors who will linger over each piece and contemplate it, instead of simply walking past it. Vhils was able to meet the challenge: he replicated the speed of the outdoors using moving image and sound, he reproduced its monumental scale by making a Styrofoam model (so big that we had to climb up ten metres to take it all in), and he designed a “semi”-urban walking route which introduced a different work technique for each space. The way in which political and advertising posters (overlapped over months and years of collage) can give way to faces (laser-cut and revealing different layers of bright colours), and the way in which those faces can be the memory of the different periods of a city, and be as effective as the gigantic faces he excavates on city walls is the most unequivocal measure of Vhils’ ability to say the same thing through different means, without allowing himself to become “domesticated” by the Museum.

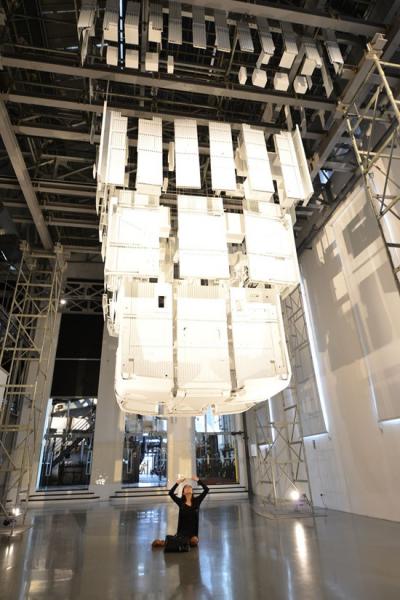

The exhibition ended with an underground train carriage (5 metres long and weighing 4 tonnes) erased by uniform white paint and by a cutting process which broke it up into hundreds of small suspended pieces. It was the most recent and the most innovative of his pieces, and it gave the exhibition its theme (Dissection), simulating an exercise of observing and analysing the urban body par excellence (the carriage provides connections within the city, and between the city and its suburbs). At the same time, it meant a return to the origins of his work and to the beginning of his urban awareness. I would have liked to have met him as a teenager, painting carriages deep into the night, dodging security guards and policemen, rehearsing a form of public intervention which he says he learned in Seixal (where he was born and where he still lives now). He would look at the 1974 political murals which endured the passing of time, as their colours and messages aged, realising they were gradually being replaced by advertising posters, and thinking about how to rescue them and project them into a contemporary future.

You don’t realise straight away that Vhils has a special character.

Perhaps that’s precisely the secret of his leadership and magnetic quality. Everything happens naturally – or he makes everything happen naturally around him. Suddenly, we realise he’s friends with the most relevant musicians in the complex universe of contemporary urban music, who he works with, and that he pulls together artists who do the same type of work, collaborating with all of them (a joint platform, called Underdogs, includes many of them). He can be seen working way into the small hours of the morning, on top of a crane, lit by spotlights on the floor, helped by his assistants, following the design of the cutting lines with blades (used on the posters’ hard skin), or using pneumatic drills on walls’ plaster and cement. Only a few moments ago we were having steaks covered in sauce at a restaurant and spoke about the World in which he is becoming a point of reference. There is no arrogance in that conversation, no vanity: rather a juxtaposition of portraits where it’s hard to separate Alexandre Farto from Vhils, because they are the same person. He explains his “tag” saying it was the quickest signature he could think of, that it can be written without lifting your hand. I don’t know whether I believe him: there are so many other letters which can be drawn that way. There really might be multiple layers in this urban portrait after all.